Featured Artists: Miles Collyer, Marvin Luvualu Antonio, and Maggie Groat

Documentation: Yuula Benivolski

More Info: Art Gallery of York University

ILLUSION OF PROCESS

Art Gallery of York University

Toronto, Ontario

January 19 – March 12, 2017

Curated by Suzanne Carte & Michael Maranda

Surrounded, as we are, by a never-ending construction site, we’re never really sure what the end result is going to be. Just outside the doors of the AGYU, a new subway station is taking shape. We’re told that the subway is going to come. We’ve been told this one for years, and before us already it was being told. We’ve been teased with “artist’s renderings,” with photo-ops, with scale models. Nevertheless, construction seems to be going nowhere, the promise always put off another month, another year.

That’s exactly the way the built form evolves, though. Only in stepping away for a bit, defamiliarizing one’s surroundings, can we actually see change as it happened. That subway? It’s coming, it’ll come, and then … instead of stopping, the changes will continue. We won’t necessarily see them, being too close, but they will continue to happen.

The work of Miles Collyer, Marvin Luvualu Antonio, and Maggie Groat all fit together. They are not, of course, the same. Far from it. But somehow, they do fit together. Their work shares a strategy, but it’s not only that.

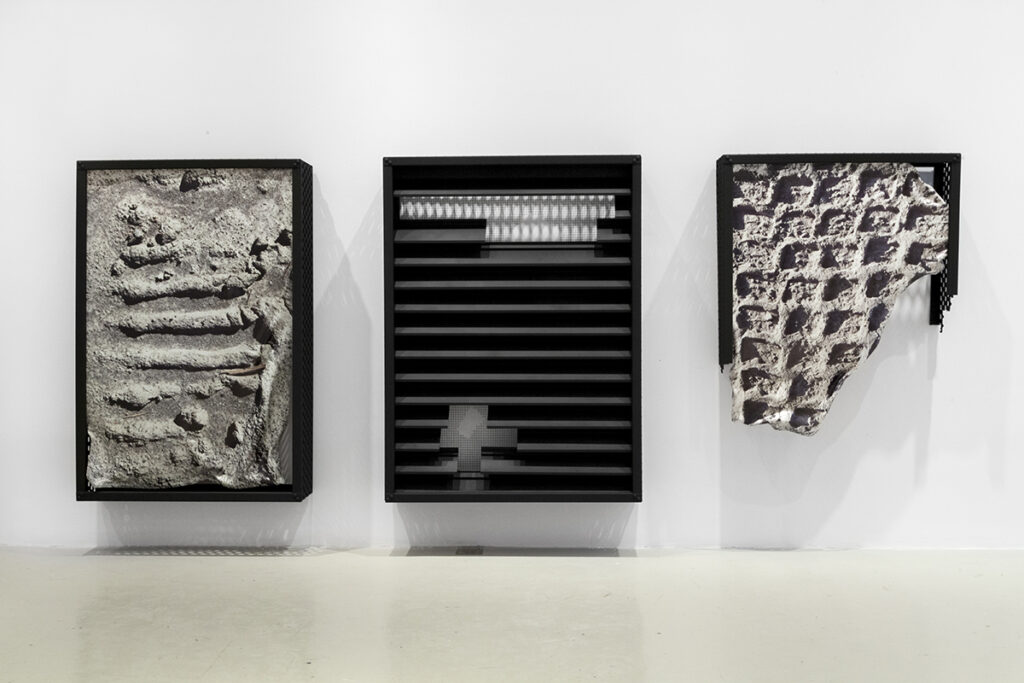

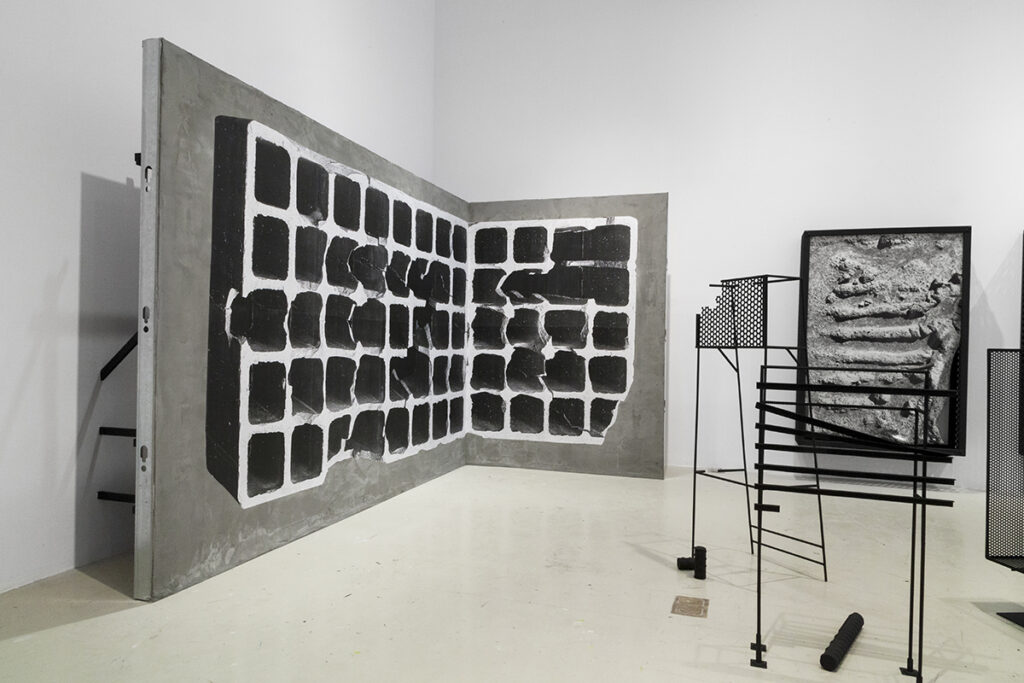

To start with, Miles, whose work appears to be about violence and the destruction of the built form. Of more importance, however, is the route that he takes: he is not representing violence, either to or for us. His source material is not crumbling concrete and twisted rebar: instead, it is the incidental representation of such. Fragments caught in the background of the evening news; snippets of real destruction mediated for our consumption as spectacle. Aspects of warzones, in a constant state of de-construction, are re-constructed in the gallery as new objects of contemplation. Miles is offering us the representation of the representation of violence. He concretizes for us, in the most real way possible, the mediated image. On display is the extensive materials-based research he undertakes, from a concrete wall juxtaposed alongside the gallery’s own walls, to the revealing of a lattice of support columns via a wheat-pasted, monolithic photocopy.

Marvin, on the other hand, is not so bound to mediation (although consideration of the spectacle? that he shares with Miles). Instead, he is, using the most economic of means, setting a stage on which he projected his familial history in a performance titled “Death is a Tunnel” during the opening reception on Thursday, January 19th. Chains delineate the boundary of the stage, sand defines the floor, brick and concrete the stage sets. His intention is not to represent to us a connection of him and his father across time and space; his performance is the making of that connection real, immersive, present. He occupies, and redefines, the confines of the gallery space, challenging the purposes to which he as subject is often put. After the opening, when the sound and fury of the opening performance are gone, the stage will become a site onto which the viewer can meditate on their own phantasies of wholeness.

And then Maggie, whose chosen material practice cleaves most closely to the edges of the construction site. We see discarded materials, cast-off and dejected. Or at least that is the starting point. She does, indeed, collect, scavenge, and reclaim her materials from various sites (including the storerooms of galleries) but this material is not merely recycled and repurposed. She is saving it, reclaiming it from the profane cycle of the commodity, inventing it anew on its own terms. Hers is a practice of new materialism in material form, borrowing from the past to construct a future that will then be built again in another form. Through acts of assembling, modifying, and transforming these found and salvaged materials, sculptures and collages are created as tools for determinate uses; as visions of possible futures and/or utilitarian objects to be activated for uses not yet imagined.

To return to all three together, though, their work shares not with the construction site (even if the materials put into play, the rebar and concrete of Miles, the chain and brick of Marvin, the detritus of cultural-products past of Maggie,) but rather with the site of the construction site. More specifically, the hoarding around the site. And even more specifically, the artist’s renderings that adorn that hoarding, whose promise is the future, the ideal, and an end to the endless rearranging and shifting, the uncertainty and noise.

Certainly, they borrow from the construction site (one can think of their studios as reserves of material to be deployed), but once the work is installed, it takes on the timeless quality of a rendering—the finished product in preternatural stasis. The illusion is two-fold, then. An illusion of finished state, of existing just-so for an undetermined period of time, fixed as it is. Then, the illusion of the process, the various components in an unending dance, a dance to which we pretend to have access. Put in another way, we see the stasis in the work on display, but the stasis promises that solidity and permanence is always … impermanent.

As is our ongoing relationship with the city in which we live. At any one point, the urban environment is fixed and eternal, but at the same time, it is always changing, at a pace just slow enough to escape detection.

Departing from the formal qualities of the material these three artists use to deconstruct and reconstruct monuments and sites, the urgency of meaning is inherent in the building materials they use. The abstract collection of matter and objects transform through use and proximity, articulating the complexities of built space and the never-ending construction of meaning. Political discourse is inherent in all of these artists’ work without the articulation of overt narratives, allowing the power of the conditional material to do the heavy lifting.

As for that subway, it is coming. We can feel it.

Marvin Luvualu Antonio, Death is a Tunnel, 2017 (excerpt)